Misconceptions from the top:

A strange development seems to be unfolding in the face of the climate crisis. Whilst many people remain indifferent (or in a state of denial), they’re simultaneously becoming passionate advocates of ‘overpopulation’ – the notion that there are simply too many humans on the planet, and that this forms one of the most pressing environmental issues, if not the issue, of our time.

As a general rule, when disengaged or relatively apolitical people suddenly advocate passionately for an idea, it’s usually a notion that’s been given to them from top-down. This might sound condescending, but reflect on how many times you’ve heard someone dismiss climate initiatives by saying something akin to ‘it’s all China’s fault’. Such misconceptions are widespread, and they’re far from accidental. Instead, they almost always owe their existence to concerted efforts by the media and the interests it represents.

Over recent years, Britain’s much-loved David Attenborough has become increasingly outspoken about climate and environmental impacts. The central cause of his concern, however, is overpopulation. Statements such as “either we limit our population growth, or the natural world will do it for us, and the natural world is doing it for us right now” have reached audiences of millions, voiced by a trusted, well-mannered biologist. Attenborough has expressed his position as “I have no doubt that the fundamental source all our problems, particularly our environmental problems, is population growth”.

These are extraordinary claims. What’s more extraordinary, however, is that they’re rarely (if ever) challenged for being what they are – wholly untrue.

Malthus from the ashes?

Thomas Robert Malthus published An Essay on the Principle of Population in 1798. In it, he presented the simple, rather alarming notion that human populations tend to increase at a faster rate than their means of subsistence. In other words, population growth would inevitably entail widespread resource depletion, causing society to descend into famine, war, and collapse.

Malthus’ predications failed to materialise. Technological and scientific advancements, particularly within agriculture, enormously increased yields. Moreover, during the post-war period, life expectancies soared, diseases were conquered, and millions enjoyed rising standards of living (despite significant population growth). Areas of want were, and remain, a product of wealth inequalities, imperialism, and a geopolitical status quo that enormously favors ‘Western’ nations; as opposed to an irreparable, inherent form of resource depletion.

Malthus’ ideas nevertheless continue to captivate. It’s not difficult to understand why. It’s estimated that the global population reached 2 billion in 1927. By 1999, it stood at six billion and, recently, it reached 8 billion in 2022. No one can deny that this represents an enormous growth in the total population, and during a mere footnote in the history of a species thought to be 300,000 years old. The figures are, frankly, dizzying. We occupy a very, very different word to the one in which our grandparents grew up in.

Despite these figures, it’s now generally agreed that the human population will stabilise by the end of the century. The Institute for Health Metrics and Evaluation currently projects that the global population will peak in 2064 at 9.7 billion, and decline to 8.89 billion by 2100. Indeed, the global population growth rate peaked at 2.2% per year in 1963 and has since declined.

Notably, China recently recorded that its population had actually fallen for the first time – a major demographic development in the world’s most populous nation. It joins a growing list of societies increasingly alarmed by the sheer pace of the shrinking size of their respective populations. Such declines are, generally, a product of the emancipation of women, access to contraception, and political and economic stabilisation.

Anti-humanism and misanthropy

Unsurprisingly, Malthus’ theories and predictions proved to be immensely popular amongst the wealthy and powerful. Fears of a proliferating working class or ‘inferior’ peoples informed the development of all manner of eugenics and racialist movements. Malthus himself was by no means immune to this thinking. Commenting on the Potato Famine in Ireland, he said “to give full effect to the natural resources of the country a great part of the population should be swept from the soil”.

The ‘problem’ posed by overpopulation inherently lends itself towards authoritarian and discriminatory ‘solutions’. Which is why it’s utterly unsurprising to find the theory take on a new life amongst the far-right, informing both the inherent logic of neoliberalism and so-called ‘eco-fascist’ ideologies. That so many right-wing commentators find it so easy to propagate overpopulation narratives (and the need for tough solutions), whilst decrying the ‘authoritarianism’ of initiatives like ULEZ, is always lost on them.

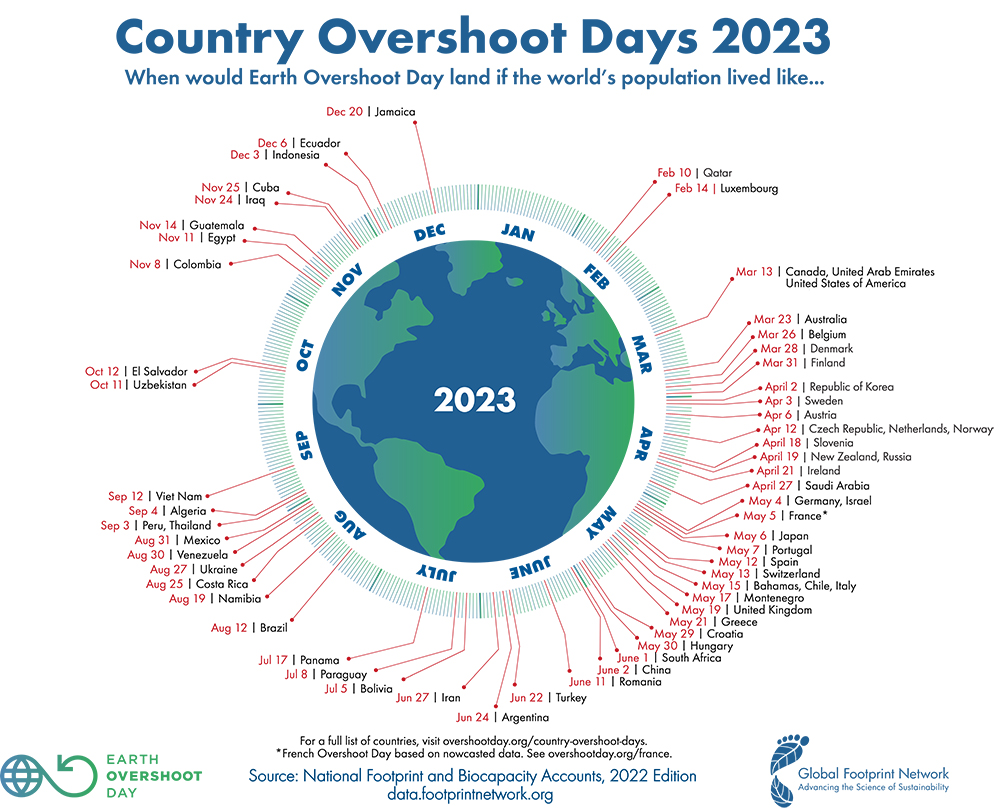

Advocates of overpopulation theories overwhelmingly present human beings as the problem, portraying the species as a parasitical entity that simply won’t stop gorging on the planet’s biosphere. The result is a politically illiterate understanding of the existing economic and political order, which entirely ignores how resources are exploited, commodified, and distributed in a capitalist economy. It also ignores the disproportionate impact of Western consumers. After all, a two-person household in the US has an infinitely greater impact on the climate and natural world than an eight-person household in Mali!

Image: Earth Overshoot Day: Country Overshoot Days 2023 – Earth Overshoot Day (footprintnetwork.org)

The unrelenting pessimism and misanthropy of overpopulation narratives effectively puts an end to any calls for action, too – why take up the cause for a sustainable planet, after all, if the species is inherently and unavoidably prone to overconsumption? It also cultivates liberal obsessions with personal climate footprints, lending itself to the ecology of paper straws, meatless Mondays, and shower caps. This entails a deprioritisation or complete negation of the roles played by the likes of the vast hydrocarbon, cement, and animal agriculture industries.

Murray Bookchin, in his essay ‘The Population Myth‘ summarised all this by stating ‘the most disquieting feature of deep ecology theorists, Earth First! leaders, eco-mystics, and eco-theists [overpopulation advocates of the era] is the extent to which they nullify the importance of social factors in dealing with ecological and demographic issues — even as they embody them in some of their most mystified middle-class forms. This is convenient, both in terms of the ease with which their views are accepted in a period of social reaction and in the stark simplicity of their views in a period of naivete and social illiteracy’.

Ultimately, we live in a capitalist society in which the entire orientation of our civilisation rests upon an insatiable growth imperative. Production is governed by, and in the interests of, a miniscule class of capitalists. Under such a logic, a total population of fifty million is just as unavoidably headed for disaster as one composed of 15 billion. In which case, overpopulation narratives are, effectively, meaningless.

This is entirely ignored by the likes of Attenborough, who refuses to examine the deeper causes of ecological and climate crises. Whilst such positions are sometimes sincerely held by their advocates, their errors have very serious consequences for anyone concerned about the future of our species.

Legitimate questions surrounding population

Despite the dangers and misconceptions of overpopulation, there are legitimate and nuanced enquires regarding population studies. For instance, it’s perfectly legitimate to consider the carrying capacity of specific ecosystems, predicated on scientific enquiry and a concern for human welfare (as opposed to a general, emotionally driven, and unfounded apocalypse scenario).

Then, of course, there’s a question of the social impacts of population. Densely populated areas, for instance, can present concerns about atomisation, the erosion of communities, noise pollution, air pollution, a lack of privacy, etc. Such enquiries are typically informed by a desire to improve the human condition, to consider how best we might live, both alone and as a part of a wider community or society.

These legitimate areas of questioning are distinct from overpopulation narratives, in that they centre human wellbeing, place demography in historical and political context, and (most crucially) don’t redirect blame for environmental crises away from their true causes and towards the innocent.